As Punter arrived for his shift, he saw his floor boss outside muttering to himself and smoking more aggressively than usual.

“What’s up boss?”

“That idiot upstairs. He doesn’t know molasses from his asshole.”

Although haunted by the image his boss had conjured, Punter understood he was lamenting Augustus Zuckerstiefel Junior, the current president of Leghorn’s Old Timey Molasses. The company, founded in 1934 by the original Mr. Zuckerstiefel, which started with one man selling maple syrup tapped from city park trees, ended up as one of the largest molasses interests in the country. Over time Zuckerstiefel bought up cheap land in Louisiana to grow sugar cane he then shipped north in his own rail cars. He burned spent cane stalks to boil the syrup, then transported the bagasse ash back to Louisiana, selling it to a local soap maker.

With a steady supply arriving by rail, sugar cane ceaselessly went in one end of the plant, and Leghorn’s Old Timey Molasses came out the other. But a drop in market price caused the company to hold onto the syrup for months rather than the usual weeks. With each of the five warehouse-sized tanks filled to the top, the pressure was mounting. Most of the time the molasses was stored briefly to cool, then pumped to the bottling room. This had been the process since the fifties when out-of-work munitions riveters constructed the tanks. They were never more than half-full and even then, only one at a time.

The number of tanks allowed time for each to be steam-cleaned between loads. No regulatory body inspected the tanks, so Leghorn’s Old Timey slapped on occasional coats of paint and hoped for the best. Thus, nobody knew what to expect as the tanks continued to fill. So too, they weren’t sure how the vintage containers would fare in the winter weather.

As any floor boss knew, molasses is about twenty percent water, but the high sugar content makes it very slow to freeze. This is what Augustus Zuckerstiefel Junior was counting on, but because he inherited his position from his father, he had no floor experience and failed to realize that although molasses rarely freezes, it does expand.

Tank number four was the first to go, breaching like an overstuffed pita. The pressure opened a crescent of brown terror moving at a snail’s pace, but the force of the listless goo caused tanks two and three to dimple, then crumple like beer cans underfoot at a frat house. A minute later the last two tanks failed.

Alarms rang through the plant. Punter, along with the other workers and bosses, rushed to stem the tide of pitch-black ooze surrounding the plant, but the doors stuck fast—they were too late. The lazy travail rose up against the windows, which finally burst in a spray of sticky shards, as giant fingers of molasses reached into the plant. The men sprayed scalding water on the advancing muck, but could only carve out divots before the floor drains were overcome.

As the relentless woe entangled their feet, Punter cried out, “To the stairs!” leading the workers to the second floor. They struggled mightily against the viscous beast, in the end saving every man. Augustus Zuckerstiefel Junior hid in his office behind a bolted door. Through the break room window, the men looked on helplessly as the treacle malediction advanced on the surrounding neighborhood.

***

Some opined the cold molasses was a blessing because one could sidestep the lackadaisical danger as one would an unpleasant finding on the sidewalk. But the crushing force of the sticky-sweet sludge made up for any lack of speed. The indolent tribulation toppled telephone poles, carried cars like an advancing glacier, and pulled homes off their foundations. Despite the time allowed by muck’s unhurried pace, attempts to alert the public found little purchase. Taken as a prank or publicity stunt, few paid any heed—the Amber Alert system was no match for the ebony tide.

The slow approach of the danger also caused over-confident victims to eyeball the creeping front and out of curiosity reach out with the edge of a shoe or a fingertip to test the blob’s mettle, only to be trapped like flies in a gluey ribbon as they twirled around a truck stop restroom. Their appendage now entangled, the molasses advanced to pull unheeding victims into the maw of the all-consuming, languid goo. Here and there, struggling forms could be seen breaking the surface—impossible to tell whether it was human or animal. Like a T Rex in a tarpit, the thrashing forms would relent in slow motion, disappearing into the sticky dread. As the mahogany madness consumed more and more citizens, officials at last issued formal evacuation orders.

***

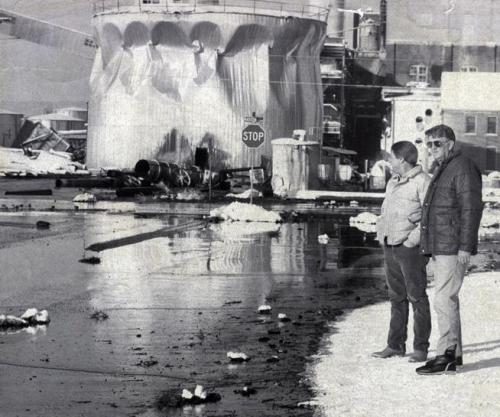

It took a week for Leghorn’s Old Timey to finally settle into a knee-deep puddle covering twenty city blocks. Debris mixed with the sweet affliction plugged the storm drains and sewers requiring removal by National Guardsmen with military-grade drain snakes. With the drains clogged, water couldn’t be used to eliminate the molasses, so police, fire crews, and volunteers scooped shovels and backhoes full of the tarry torment into dump trucks. They made gradual progress, and recovered victims looking like Pompei captives glazed with spent axle grease.

The community turned to the plant workers for help in cleaning up the residue of the unhurried calamity, but they’d never seen a spill of such scale.

“At most, we’ve cleaned up a barrel or two, but not an ocean!” The floor boss complained. “If you can’t hose it, you’ll have to wait for some rain to dissolve it away.”

“We could burn it,” Punter said.

“You can’t light molasses boy; the match will just fizzle out!”

“We could use blowtorches. The molasses will burn away into dust.” With the help of National Guard flamethrowers, arcs of burning fuel lit up the inky lake, turning it to ash. The stench of burned sugar lingered for years. For decades, not even a weed would grow in the ruined soil.

***

In the aftermath of the disaster, the mayor and city council pursued compensation from Leghorn’s Old Timey, but Augustus Zuckerstiefel Junior had fled to Argentina. He bought a sorghum plantation, and while making an embarrassing effort to hit on his interior designer authorities apprehended him. They informed Augustus the US had a well-established extradition treaty with Argentina and not even Nazis were safe there anymore.