Teddy was typing at top speed–just over ten words per minute. He feared an error that may cause him to start over by melting his block of letters. Fifteen months on the linotype and he was no faster than the day he began, but he seldom made a mistake. In the time he could complete a paragraph others completed three or four, including the time it took to correct any typos. Paid by the letter, he preferred the surety of going slow to the risk of making a mistake. The floor boss put him in the check printing section, where accuracy was more important than speed. Teddy made less than anyone else, but the reliable, steady income gave him peace of mind.

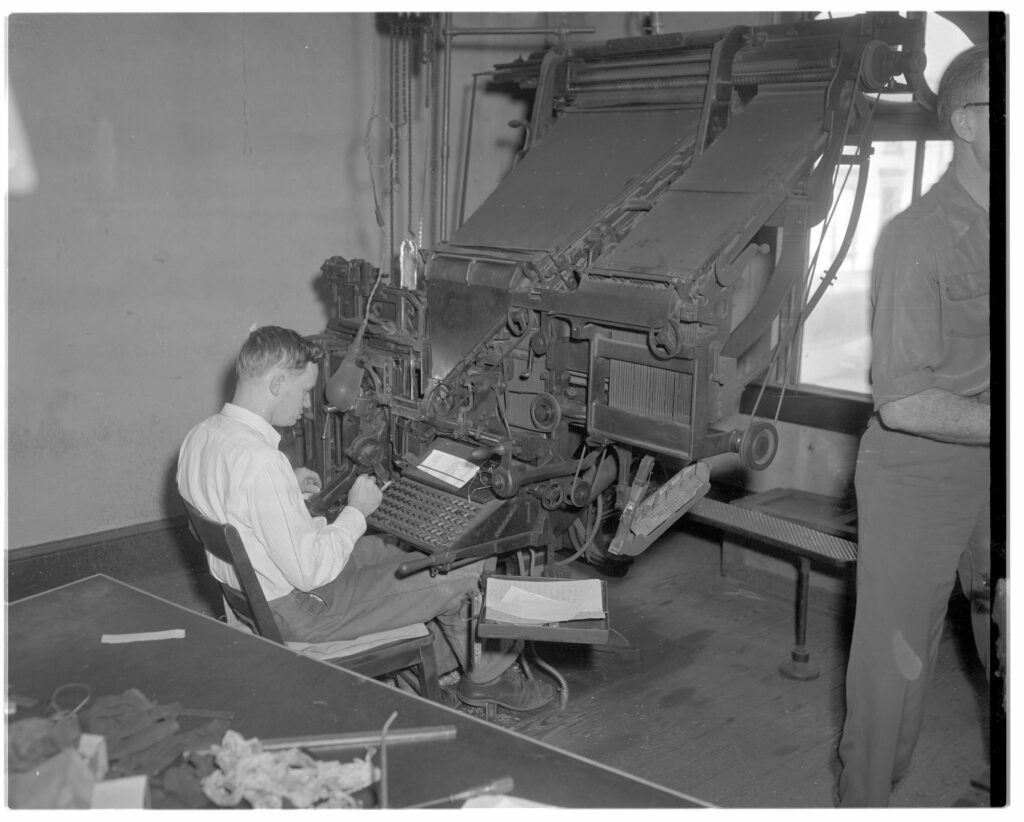

Cooper Printworks churned out every type of printed material: textbooks, pulp novels, fill-in-the-blank legal documents, labels of every kind, advertising flyers, and both personal and business checks. Paper and ink flowed in one end and printed matter out the other. Inside a vast assortment of semi-automated machines with massive gears and levers spun with brute force precision. The uncirculated air was thick with the smell of hot grease, sweat, and fresh ink. Teddy was a linotype operator, along with dozens of others, toiling on twelve-foot-tall machines that clacked and whirred churning out lines of lead type. A three-foot-long ingot of lead hung from a hook, slowly melting into a gas-fired tank. As the linotypists punched out letters on a giant keyboard, brass molds with reversed letters dropped in line. When a line was complete, hot lead squirted into the mold, and seconds later, a fresh line of type dropped out. The tank of hot lead made the work a blessing in the winter and a curse in the summer with Cooper Printworks lacking any environmental controls. It was during an exceptionally hot summer when Teddy ran into trouble.

The cool kids of Cooper Printworks worked on pulp novel row. Back when computers required punch cards to count to ten, the fastest way to crank out softcore sex and violence was the pulp novel. Employing hundreds of alcoholic copywriters publishing houses with names like Rocket Books, Black Hood Books, Lead Pipe Publishing, and others moved literary meat through the proverbial sausage works with the speed of an efficient slaughterhouse. They needed skilled linotypists to keep up with the rushing flood of prose. The pulp fiction boys had the fastest speeds of any typists and accuracy–just over eighty percent, which was good enough for the pulp fiction market. The coarse paper yellowed and binding glue failed as soon as the books hit the shelves, but the novels delivered cheap thrills as quickly as the readers could burn through them. The pulp fiction market was a significant profit center for Cooper Printworks, with the linotypists often working late hours and greasing their productivity with oily gin. Teddy was on his way to the bathroom when he ran into a group of them. One gave him a sharp elbow as he passed, which Teddy ignored, trying to stifle his grunt of pain.

“What’s wrong, check boy? Cat got your tongue?” said Hugo, the leader of the pack. Teddy ignored him and tried to push past to the bathroom. “I think you’re heading into the wrong one. That’s the men’s room!” He shoved Teddy, knocking him to the floor covered in paper dust and printer grime. Teddy heard the boys laughing as they returned to pulp fiction row. Dusting himself off, an angry fire formed in the center of his mind.

Coming into the spring of that year and through mid-summer, the pulp fiction boys picked on Teddy more and more. They were many, and he was one, so he kept turning the other cheek until finally one day in mid-August, he reached his limit. The outside temperatures hovered around one-hundred degrees, and the linotypists wore headgear of every kind trying to slow the sweat streaming into their eyes. Fainting was common, with operators listing, then slumping onto their keyboard. The floor boss would signal nearby linotypists to carry their fellow to the cool of the bindery basement to recover.

The pulp fiction boys became bolder and bolder, and management let them be so long as they kept on grinding out novels. They harassed the women, mocked the men, and as their type often do, fixated on Teddy. They wanted to break him. To drive him out or at least draw him into a fight where Hugo could take him to the cleaners. Had Teddy done something to deserve their ire? He was the weakest and the slowest and was easy prey. That’s all it took.

Teddy hoped if he ignored them, they would get bored and bother someone else: the shared dream of the bullied, and bad advice from parents throughout the ages. Fighting back wasn’t an option as Teddy was outnumbered, outsized, and barely knew how to throw a punch. He was as surprised as the Pulp Fiction boys at how things turned out.

The heat pressed in from all sides and no air moved through the printworks. Dormer windows near the ceiling let in more heat than they let out, but closing them was inconceivable. Teddy had three handkerchiefs tied on his head to stem the flow of salty water into his eyes. Sweat beaded on his fingertips, making the keys slippery. The heat caused the linotype machinery to expand, leading to jams. On Teddy’s machine, the feeder that dropped brass letters into the molds was stuck fast. He had to hurry and get them moving lest the valuable brass molds could be damaged. As he stepped on his chair to reach up and loosen them, a seal in the lead melting tank popped open, and a stream of hot lead shot onto Teddy’s foot. As he jerked his foot away, he began to fall off the chair, his hand clutching at the brass blocks to save himself. He crashed to the floor, splayed out in defeat, the chair skittering away as he howled and kicked at his foot to remove his lead-covered shoe. Covered in sweat, the grime of the floor coated him head to toe. Despite the heat, the fall, the burning foot, and stinging eyes, Teddy still clutched the valuable brass letters in his hand. He was slightly lifted out of his despair by the small glimmer of achievement in protecting the expensive brass molds. As he started to lift himself from the floor, Hugo happened by and shoved Teddy, causing him to fall.

“Watch where you’re going, faggot!”

In a single movement, Teddy leaped from the floor and smashed the brass blocks into Hugo’s head. Hugo reeled and Teddy kept at him, kicking and punching and screaming. Hugo fell, and still Teddy kept on, landing blow after explosive blow to Hugo’s face and head. Shocked by the speed of Teddy’s violence, the other Pulp Fiction boys were slow to act but finally pulled Teddy off and tried to assault him in kind, but Teddy’s wildness overwhelmed their resolve. They pulled back like men afraid of a rabid dog.

Some of Teddy’s fellow checkbook typists calmed and sequestered him to the basement men’s room. In the dim light, Teddy saw himself in the mirror. Covered in black grime with skin-colored streaks where sweat had flowed. His eyes wide and his chest heaving, he noticed he still held tight to the brass letters. It was a collection of ampersands, quaking like aspen leaves in his hand still trembling from the adrenaline. He noticed they were stained with blood and started to wash them off in the sink until someone gently told him to stop. They told him Cooper Printworks would likely fire him and the pulp fiction boys might kill him, so he had best leave and never return.

Teddy left through the basement exit, suddenly met by the blazing light and heat of summer. He was still missing a lead-scalded shoe but figured little point in going back for it. He paid a nickel to wash up in the bathhouse, limped home, put butter on his foot, and tried to sleep. Sweat pooled into his navel or if he turned over the small of his back, and his mind reeled. Violence was new to him and he didn’t know what to expect. He liked things calm, predictable, reliable. He sat at the small table near the window in his kitchen on the third floor. The rumor of a breeze moved the curtain and the air gave Teddy some hope. He looked at the newspaper and noticed an ad for jobs out west with the railroad as a telegraph operator. Because he could read, write, and type, he quickly found work in San Francisco with the transcontinental rail line. He still worked with machines and monsters but was happily tucked away in his telegraph office, where accuracy was the gold standard.